Isa (One).

When you look upon a seascape painted by Joar Songcuya, you can almost feel all that space and time, empty yet heavy, bearing down on you. He spent nearly a decade, most of his adult life, at sea, and used the spaces in between his grueling, often dangerous work as a marine engineer to teach himself to paint, a painstaking process he so generously shared with us during his artist talk. When you see it, you just know that each stroke is earned, shimmering with the traces of the passage of unfathomable miles and minutes, the failures and the triumphs, both.

We praise our seamen as heroes, and even we at Emerging Islands are guilty of romanticizing our submerged history of seafaring in our attempt to reclaim it, but the sea is an environmental frontline nonetheless, demanding sacrifices our country can never repay. Joar went to sea for his whole family back in his hometown on the coast of Iloilo, paints about the sea for them, still: house upkeep for his aging mother, college classes for his kid brother, sending support and souvenirs from wherever in the world he goes. Even in our residency, Joar continues to fill all the empty spaces with thought and care for others: painting classes for the kids who live on our street, and merienda for the community who came through our doors to get to know Joar and his art. Whenever we can, we remind him to give as much to himself.

But in meeting the sea with all of the phases of his own inner state, in loneliness and love, in anger and joy, in rage and despair, in desperation and peace, Joar’s also been on another journey—that of shaping what he sees when he looks upon himself. In each of his paintings is another ocean, another Joar, “same same but different.”

To look upon the sea is to see time, itself, passing by, the swirl and shape of a story that is never quite finished.

~

I used the expression “same same” without thinking, intuitively referring to a saying I’ve heard Balinese and Filipino surfers use. Joar tells me that “same same” is actually maritime language. Were surfers inspired by marinos, or did the two uses of the same expression evolve separately? Either way, he’s delighted by the coincidence, and grateful, even, as he always is. Excitedly, he explains this facet of marino culture, and his own experiences at sea start to unspool:

“It’s pronounced as ‘sem-sem’ or ‘sim-sim’ by Pinoy seamen and adapted by foreigners too.

The engine space, where I have worked with for a decade has an engine and machinery noise of 170 to 200 decibels—160 decibels can already injure the human ear.

Conversations onboard or in the engine space are always reduced to a minimum so if you are good in English you need to like readjust like how Russians or Japanese say things...

You can’t say ‘Can you please go to the workshop to get this particular tool?’ Maritime way of speaking: ‘Go, work shop, get (gesture to the tool) same same like this.’ Sometimes it’s reduced to just ‘Same same’( pointing to the tool )

So we talk in primitive English, in gestures—with earmuffs :) Ang marino may sariling lingo pala kami.”

Dalawa. (Two)

andi arrived in the Philippines in the midst of the rally that filled the streets of Makati, and travelled to La Union on the day of elections. The day after the election results came out, we met on the beach to watch the sunset. The conversations we had were heavy, circling around a gap we didn’t know how to bridge, in the shape of a question we didn’t know how to answer: What does it mean to be Filipino? What does my being Filipino have to do with other Filipinos?

Somehow in their presence, the heaviness of reality always ended up transformed. Not into something else, necessarily, but into something that could be worked with. A concern about connecting with our community turned into an afternoon of talking story with the nanays and titas who lived in our neighbourhood. A worry about the problems caused by tourism became a brainstorm on how community-based art can facilitate not only the dialogue around these problems, but ideas for their solutions. Even the very real fear about our future turned into a daytrip to Baguio, learning from Indigenous People who have found in art a way to tell their story, to be seen and heard, despite the ignorance and inattentiveness of mainstream society: the Kalinga textile artist Irene Bawer, and her life partner, Ifugao photographer Ruel Bimuwag. We were constantly forgetting to use their pronouns correctly, and yet andi would just smile and say it was okay. It almost felt like their choice of pronoun was an invitation rather than a declaration–a way to get people to see more, engage more, make space for more.

After andi finished their artist talk, someone asked a question about how to find a sense of belonging when it feels like a place and its people won’t let you in. They answered about how, in everything that they do, they ask two questions: “Who is not here with us?” and “How can I be there for you?” Their art practice is a living embodiment of American philosopher Richart Rorty’s idea that “solidarity is not discovered by reflection, but created. It is created by increasing our sensitivity to the particular details of the pain and humility of other, unfamiliar sorts of people.”

andi comes from a position defined by what it is not: undocumented, which is their mother’s status in Canada even after decades of living there. In French, which they speak fluently (better than their Anglo-Canadian partner, but nbd), it’s said as “sans papier,” to be without identification. Is who we are so paper thin? Is this question unanswerable, in the end? andi’s gut response to the unrelenting threat of erasure surprised us. “I feel whole,” they said simply, their smile sweet but assured, and somehow I felt held in all the parts of me that don’t believe this to be true.

Tatlo. (Three)

We see artists come and go. In a sense, every story told of these islands is a journey of coming and going, mapping out a path of unrepeatable moments. But sometimes, two paths meet somewhere in the middle, and that’s the story of Joar and Andi, who, as the winds of fate would have it, were in our residency at the same time.

Each carried with them different variations of the Filipino story that is diaspora, the family-driven search for better horizons. One arriving, the other returning, both in search of a sense of place, which is in its way, a search for home. And yet somehow, together, they made more sense of the work we do, made more space in our house, and gave more life to everything they touched–simply by being in the same space.

Seemingly overnight, the house was transformed by a flurry of activities, conversations, and materials. We could only just about keep up with all of andi and Joar’s plans. It was beautiful to witness how two people can hold space for each other, offering not just presence but permission–to play, to perform, and believe in our own promise. You could say that Joar’s sensitivity to others is a matter of his provincial Ilonggo upbringing. You could say that andi’s is a matter of growing up in Canada as the daughter of an undocumented Filipino. Or you could say that empathy is what grows between two humans who see each other as such.

Finally their collaboration came together on their shared open studio day. Joar recreated his ship cabin-cum-art studio, practically overnight, and, of course, made sure to invite the whole neighbourhood. He offered everyone who walked in our door a paintbrush, asking them to paint either their home or the sea. In between helping children mix colours, he flitted about the house, charming and soothing everyone around him. You’d never guess how nervous he was.

On that day, all the ways that andi can already see possibilities in the world around them, each calling out joyously for our attention and care, came out to play. Their kid Caio danced with the flashing lights of the projector, while their partner Adam, a graphic designer always ready with a dry joke and a ridiculously resonant laugh, took photos. The highlight for me was a pungent pile of broken fishing net they were given by a fisherman, which they (with Adam, Joar, David, and Jomar’s help) raised into the air, transforming it into an audio-visual installation about the sea.

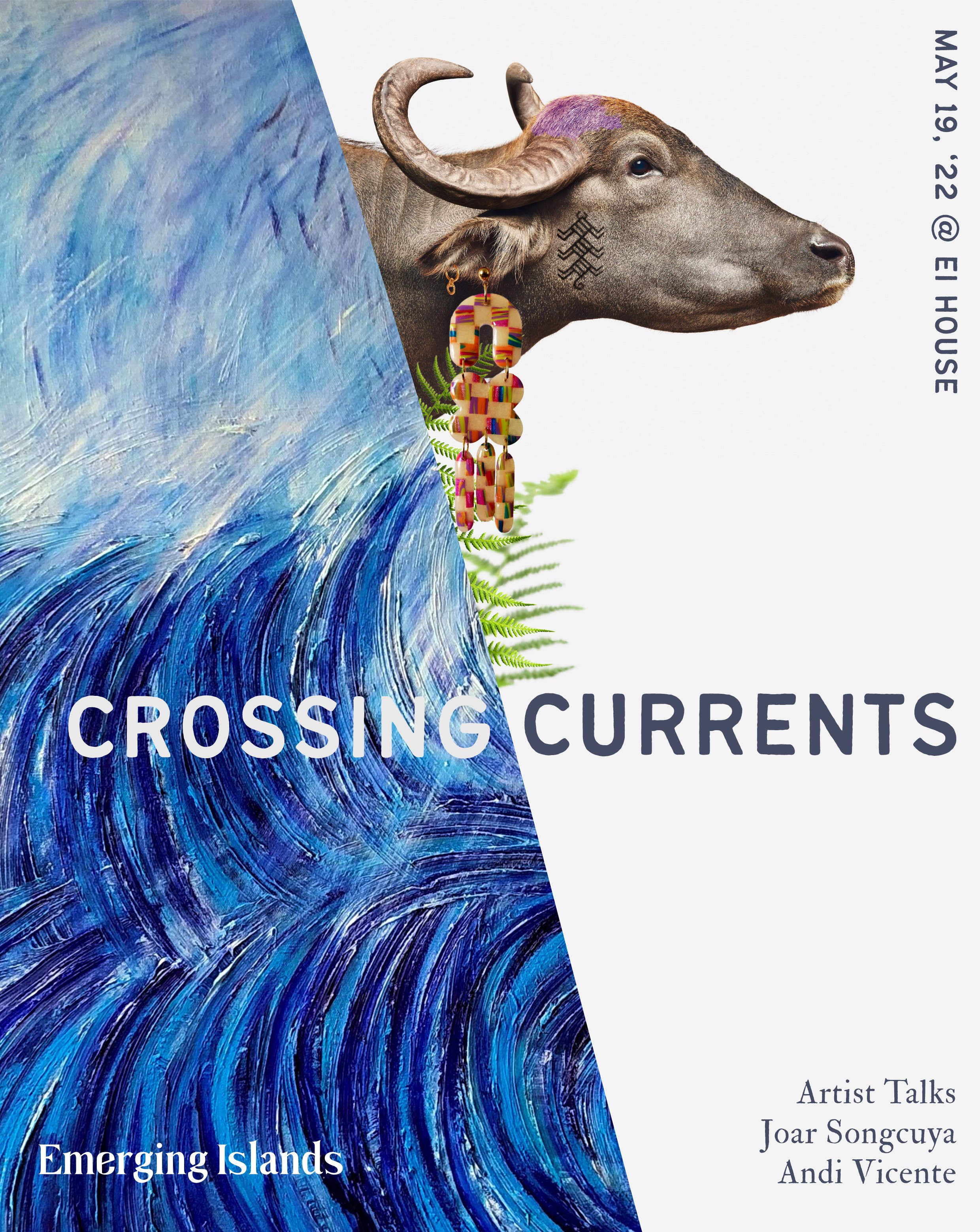

It wasn’t just that we felt like a family, however transitory and makeshift. It was that we recognised an answer to our question. Being here, together, felt like a more whole picture of Filipino-ness. We named their joint artist talk “Crossing Currents,” and that became a motif running throughout their shared residency. The Filipino story is migration, is departure, is balikbayan, is OFW, is TNT. We are all of these stories, a cacophony of voices all speaking at the same time (thank you for this idea, poet Lawrence Ypil). After all, these islands are shaped by the currents that move around them, through them. We are all of these islands, scattered, gathered.

~ Nicola Sebastian